it wasn't the usual feeling of being suddenly alert; something physical woke me  Stick with me on this one, it's not another space jaunt even though it may seem to start out that way. Although... I get up early every day, typically between 4 and 5 AM, sometimes earlier. This morning I woke up at 2:30, and I've learned when that happens to just go with it. Left to its own my body seems to need about five hours' sleep most nights, though sometimes longer. There's no reason to fight it with my flexible existence down here. But this morning it wasn't the usual feeling of being suddenly alert; something physical woke me. I'll get to that in a minute. The first thing I noticed, once I realized that, yes, I wasn't going back to sleep so I may as well get my feet on the floor, was a light outside the house. We have a motion-sensor flood light in the yard, and when it goes off in the middle of the night it's typically a deer wandering through. It's not intrusive enough through the bedroom windows to wake me up by itself, but it is plenty bright. And the light I could see being cast downstairs from the kitchen was too bright for any natural light. Except it wasn't. You'd think after four years I'd recognize it, but it turned out the security light was not on. No light was. What I was seeing was coming purely from the Moon. That's how dark the night sky is here. It's shocking when you come from a city that never truly sleeps, unlike Brookings where there's not a single 24-hour business in town. But don't get the impression our house is swathed in black. It never is. The yard is completely surrounded by rain forest so thick we can't see any of our neighbors' homes, but even on moonless nights, the starshine is enough to make out most features on the property. When the Moon is out you could literally read by it. It has fooled me into thinking the flood light was on many times, but even so, it's so unexpected that it still catches me after all this time. But it wasn't the Moon that woke me. I had been dreaming of a skiing trip with my grandfather who passed away in 1999. We were just headed to the slopes, and he was handing us all something--it looked like a chunk of dry ice, though I'm not sure why that would be. Its purpose though was clear. The ski resort was at high elevation, and breathing the fumes coming off these chunks made up for the paucity of oxygen and let you breathe normally. My grandfather was that kind of man--generous, no-nonsense, and always prepared. When I woke up, the reason for the dream was apparent. One of my sinuses was so closed up I could only breathe on one side. A few minutes of traipsing around the house upright cleared that, and I was left with the dream's deeper meaning. I held a special fondness for my grandfather. I mentioned before that he was the only person who ever read my first novel manuscript. But that wasn't the source of my regard. He was the most fearless and forthright man I ever met, imbued with unshakeable integrity. (Happily, those traits were inherited by my father.) He could seem harsh, but only because he always spoke the plain truth. And the truth hurts, as they say, at least a good share of the time. Our personalities were fiercely opposed, but we still had a lot in common. He was a huge fan of science fiction, which now seems anathema to his knothead-intolerant demeanor. In fact it was he who turned me on to sci-fi, in the form of paperback novels left on a bookshelf in a lakeside cabin he built with help from my dad and his brothers. I still have two of those books that I stuffed in my suitcase at the end of a visit there. A decade and a half later, my grandfaher's absence still leaves a void in the world. I wish he could have met the man I have become. I hope someday he will. -Mark

1 Comment

There's no chance I'll get rich from The Just Beyond any time soon, so yeah, I still need to work the consulting gigs. The blog took a rest the past few days, and regular readers may be wondering why. The immediate reason is that I got about 3/4 the way through a post concerning my feelings about art, specifically a particular feature of some art that I find highly annoying, and I realized I wasn't satisfied with the way I was describing it. Whenever you criticize any piece of art, or genre, or type of content, you are guaranteed to offend the people who appreciate that very thing. And it was important to my point to make sure that, while I don't expect nor even desire to change anybody's opinion on the matter, it was important that what I was saying at least be understood. So I put off finishing that, and I had spent 11 hours doing field work for my consulting business that day so I ended up too tired to knock it out, and then the weekend came and it just got set aside. It still isn't done, but the draft is out there and I'll post it when I'm content with the end product.

There's no chance I'll get rich from The Just Beyond any time soon, so yeah, I still need to work the consulting gigs. :) Two fairly involved ones came up last week and I spent much of the weekend working on them. Aside from that, I've been testing a new computer game creation tool, which comes with The Legend of Grimrock and is the perfect platform for making games like the much-beloved Eye of the Beholder dungeon crawl. And I've been playing Far Cry 3, the sequel to one of my all time favorite games. You may have noticed a nonfunctional link on the main page to a "Far Cry 2 Play Guide". I plan to complete that when time permits too. So there's a lot going on, and though I've been shocked at how pleasant blogging has been for a guy who generally dislikes writing at all, it's impractical for me to post something new every single day. I will do so whenever I can--the whole point of this website is to develop interest in the book(s)--but putting something out there just because the clock is ticking would inevitably compromise the quality. So keep checking--when I do add new posts I will do my best to make them worth your time. If you've miss these posts and haven't read them all since the first one released at the beginning of this month, you can always look at any of them either by paging down or using the sorting tool at right to bring up only those you're interested in. Assuming you're interested at all, something I don't take for granted and am lucky and humbled if you do. The publication process for The Just Beyond of course is still in progress, but nothing new has emerged the past few weeks so from a reader's perspective (and mine, since the publisher's process is opaque to me), it's kind of in suspension. That doesn't mean I have nothing to say, and when it's something interesting enough, it will appear here without fail. In the mean time, thanks for your patience. - Mark A billion years is a very long time--almost twenty times as long as it's been since the dinosaurs went extinct--but compared to Eternity it's not even a nit.  The Just Beyond asks what has always seemed to me a natural question, deceptively hard to answer. If there really is an afterlife and you're fortunate enough to get there...what are you going to do? The question is probed at greater length if not more eloquently in the book, but to boil the problem down, it goes something like this. When you think about it, everything we do in this mortal life is bound up with our physical bodies. Note, I didn't say everything we care about, I said everything we do. I can think of plenty of moral and artistic values we care about that seem primarily spiritual. Back to that in a moment, but to finish the first point. Suppose, as most believers do, that in the afterlife the body and its requirements are transcended. No more pain, no more injury, no more disease, no more fatigue, et cetera. Having surpassed the physical, there's no need or reason to eat or drink, or sleep, or arrange for shelter, or have sex. Presumably no babies are born in the afterlife, so that last is doubly useless. (Is that really an afterlife I want to live in? I'm not so sure. lol) You don't need money, because you don't need anything at all just to survive, so you surely wouldn't work at anything you didn't find worthy on its own merits. But would you even do the worthy things? For a while, sure, assuming you could; maybe for a very long time. If you've always loved skiing, maybe you climb the highest mountain and schuss down it one zillion times. No lift needed, you wouldn't get tired and you'll never run out of time. But what's the cutoff point? At a zillion and one, have you finally done down every possible path, had every possible experience, maybe had each of them a thousand times, or a million...does the compulsion to do this at some point stop? The same is true of any activity. How many songs can you write or paintings can you make before you're out of ideas or enthusiasm or both, a billion? A trillion? And what are you going to paint or sing about? If the Earth is behind us, the sick are made well, there's no more poverty, war, hard luck, or romances gone bad, what's your material? Even if you have an answer, how long can you stretch it out? A billion years is a very long time--almost twenty times as long as it's been since the dinosaurs went extinct--but compared ti Eternity it's not even a nit. Most people when they think of afterlife envision themselves communing with loved ones or acquaintances long lost. That is a terribly noble and worthy picture. But think about it. After a while, and I mean a long, long period of doing that...what are you going to talk about? There won't be any family secrets or celebrity scandals. There won't be any politics or issues of general concern. There won't be any news, either about the world or about you and your loved ones; given enough time, everything that can be said will have been, and there's no more coming. No marriages or births or deaths or misfortunes or runs of increble luck. All that stuff arises from the mortal human condition. I know people who imagine themselves just standing in the Heavenly pews singing praises to God as their afterlife activity. I'm not going to argue with that, it sounds nice, wholesome, worthwhile, enchanting, and probably well-advised. :) But the same analysis applies even there. Are you going to do nothing but sing in church for all eternity? Is that really what your whole existence was all about? The Just Beyond begins to answer this question, and the trilogy when complete will give the most logical and satisfying answer I've been able to work out--and I've given this a lot of thought. :). Even so, I've been harboring a terrible secret. Because I realized somewhere along the way that my answer, as reasonable and carefully constructed as it was, ultimately fell to the same criticism I've outlined above. My scenario works for a long time, a very long time, and explains everything from the purpose of mortal life to the ultimate fate of good and evil...but then, after all that has been said and done, philisophized about and settled...in comes Eternity again. And it's just about impossible to think up a scenario that truly conquers ALL time. I knew this, and I thought the books would come close enough to feel they had achieved it as far as one reasonably could, and I had set the problem far aside, on a small table in a dark basement room in another house, never to be thought about again. :) And then, suddenly, it came to me...an even better way. An answer that went beyond my hard-crafted paradigm, as full and coherent as it was. An answer that seems like it could be eternal, and if not, comes close enough to blur the distinction between perfect and very, very, very, very good. :) What is it? Read the books. I hate to leave it at that, but on the other hand this is the sort of thing, obviously, that can't be fully revealed until the final pages of the final book. With any luck I'll have that written by the end of next year. Meet you at Beyond All Else, and you can let me know how I did. :) - Mark If the Sun were the size of a basketball... Setting aside the quote above for the moment--it's not related to this question--how long would it take to walk from the Earth to the Moon? Assuming a suitable road, space suit, and a sustainable pace with breaks for eating and sleeping, of course.

It works out to about 30 years. Not bad at all. How long would it take to walk to the Sun? You'd need a good deal more sophisticated suit, but if you had one, and could spare the time... about 12,000 years. That actually surprises me in how relatively short it is given the 93 million mile distance. 12,000 ago is just about the time the first humans migrated over the Bering ice bridge to North America. If they hadn't stopped to found the Maya, Inca, and other Native American cultures, they could have made it to the Sun by now. This is the kind of thing I figure out in my head to put myself to sleep at night. You can do this one. If the Sun were the size of a basketball... how far away from it would Saturn be? :) If that's too easy by itself, work out all the planets... and what common items they would be the size of... You can do it without a calculator. :) - Mark the truth turned out to be so outlandish no one would have even suggested it.  Theia was a real planet, about the size of Mars, that orbited our sun when the solar system was new alongside Venus and Mercury and the Earth. We don't talk much about it now, because we don't see Theia as she was. But Theia is still there. It would be cool if I could tell you that Theia was obliterated in a mighty collision that blasted her wreckage into the rocky ring between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter that we call the Asteroid Belt. Alas, science has pretty much proven that the asteroids aren't remnants of a planetary explosion but just bits of flotsam left over from that same era, kept from ever forming a planet in the first place by Jupiter's gravitation. No, Theia didn't fracture into a ring of invisible smithereens. Theia's story is much more intimate to us. Theia crashed into the Earth. The Earth has been hit by large astronomical bodies many times. But this one was unique. The sheer size of Theia puts this cataclysm in a class all its own. Compared to Theia, the six-mile thick chunk of stone that killed the dinosaurs and ravaged Earth's climate for a million years was a BB. It took analysis of mineral samples brought back by the Apollo flights to reveal this amazing story. Before then, the origin of the Moon was a matter of educated speculation. The most accepted theory was that the Earth had "captured" a passing planetessimal that wandered into its gravity well by chance. There were problems with that theory, but there were worse problems with every other theory. And without physically examining the Moon up close, the mystery could not be solved. To make a long and complex story short, here's what the chemistry of the Moon rocks revealed. Some time more than 4 billion years ago, when all of the sun's terrestrial planets were lifeless worlds of fiery meteor showers and violent vulcanism, Theia and our Earth crashed together. But Theia didn't become our Moon. Earth was larger, but Theia was large enough to hold her own in the contest, and both planets were severely disrupted. Theia did shear into molten fragments, but the crash also blew out a huge section of our planet. As gravity sorted the pieces, the heavier minerals of Theia merged into the Earth, and the lighter minerals from both of them scattered out into space. It was this material--the lighter stuff from both worlds--that ultimately coalesced under its own gravity to become our Moon. The bulk of Theia is still with us...we're walking on her. :) Theia's name is borrowed from the ancient Greek Titan of Light, said to have been the mother of the Moon. In that scenario its father was the Earth itself, and now the two lunar parents are bound in an embrace that will last till the end of time. And we can thank her for our seasons. It was the Theia collision that knocked Earth's rotational axis off-kilter from the plane of its orbit around the sun, creating the variance in sunlight that changes summer into fall, winter into spring. With all the wild theories of the Moon's formation that predated Apollo, the truth turned out to be so outlandish no one would have even suggested it. Scientific discoveries so often go that way. Good fiction tries, but half the things that have been discovered in the hundred years since Einstein would have been laughed off the page if someone had made them up for a book. The cosmos itself will probably always be the world's best storyteller. - Mark It's not a particularly rare event, but I had never personally looked at it through my telescope before. Busy day today--not much time for a thoughtful post, but something fun did happen and it ties in with yesterday's piece. Our living room ceiling goes all the way up to the second story and there are two large windows high up on a gabled wall from which we can see high up into the sky. Around dinner time this evening, the sky a fading cerulean twilight, the moon appeared in those windows and very near it, what looked like a faint star. Knowing that what looks like a faint star in an otherwise starless firmament must actually be a very bright object, I wondered what it was. It only really could be one of three things: a truly bright star like Vega or Rigel, or one of the two planets that appear brighter than any star: Venus and Jupiter.

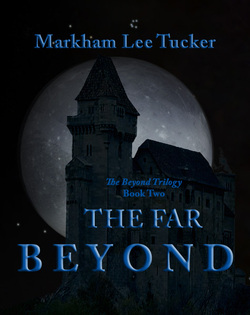

I didn't think it was Jupiter, because I tend to keep an eye on it from night to night and I didn't recall it looking like it was going to approach the Moon. But I didn't think it could be a star either; it's very odd for only one actual star to show up in the sky, but quite common for the planets to appear before the sky is dark enough to see any stars. I don't keep tabs on Venus--I don't actually study the sky on a regular basis and Venus moves too fast to really track, besides which Venus is so bright and large in appearance it's hard to mistake it for something else; there's no need to track something you will always know when you see it. But it looked a bit too high in the sky for Venus, which never appears too far from the horizon because it's so close to the Sun and in order to see it, the Sun has to be somewhere near setting or rising. So the most likely candidate was back to Jupiter, and that did make sense; Jupiter has been churning its way slowly across that part of the sky for weeks. I had to be sure though, if for no other reason than the fun of it. So as soon as it was dark enough I chugged upstairs and took my telescope out on the second floor deck outside my studio and pointed it at the spectacle. And there it was, the confirmation: Jupiter's moons. Jupiter has four moons large enough to be easily seen with an amateur telescope or even a good pair of binoculars, tiny white dots that appear in various positions around the planet like bees around a hive. I could see two of them clearly and thought I could see a third when I was able to keep still enough. And there it was, a delightful astronomical oddity--our Moon, a little larger than half phase with its mares and craters showing up sharp and crisp in my telescope, and within the same image mighty Jupiter and its own moons far away. It's not a particularly rare event, but I had never personally looked at it through my telescope before. It's just a little thing, but this is the kind of food for the soul that brought me to this little beach town in the first place. Between clear night skies overhead and the majestic thrashing of the Pacific at my feet, it just feels like this is the Place in the universe where I'm supposed to be. :) - Mark The Cygnus X1 black hole is 7 billion times the mass of our sun and has a diameter the size of the orbit of Pluto.  I've always been fascinated with the night sky. As a kid I used to take my guitar out into the front yard and night to sit on a brick step and play where nobody could hear me but the stars. It was an inspiration like no other. Now I have a decent amateur telescope, a Meade Polaris 6-inch reflector, and live in one of the least populated areas of the country where the heavens shine in all their glory undiluted by city lights. I grew up in a small town with relatively dark skies, but living in Seattle for decades I had forgotten just how brilliant and stunning the cosmic scene could be. One of the first things I did when we got settled down here was grab my star atlas and look for the Andromeda galaxy. It's the one in this picture, the iconic Hubble Space Telescope image, the galaxy we tend to picture in our minds when the word is mentioned. Among the billions of galaxies we know about, Andromeda is remarkable in several ways--unique, in fact. First, it is the closet major galaxy to our own (discounting two small satellite galaxies that revolve ours like moons). Second, it's the only galaxy outside our own that can be seen with the naked eye--though you need ideal conditions and a good idea both where to look and what to look for. Third, and this is the one I find the most mesmerizing: Andromeda is not receding from the Milky Way. It's heading toward us. The world was shocked when Edwin Hubble discovered in 1923 that some of the amorphous blobs in the night sky were actually "island universes" separated by unimaginable distance from the one we live in. The aftershock was just as great six years later when Hubble found that the univese was expanding: every galaxy in the cosmos was racing away from us at tremendous speed. Well, not every galaxy. Andromeda, of the same class and somewhat larger than the Milky Way, is on a collision course with us. It's going to happen. One day in the distant future Andromeda and the Milky Way will collide, eventually fusing into a single system with each of its constituents' original shapes obliterated by the crash. It's nothing we should worry about though: significant gravitational contact between the galaxies is four billion years away, and by that time our sun will be starting to run out of hydrogen and preparing to explode. If the human species survives to see the galactic fusion, we'll need to have found someplace else to live.) Andromeda isn't too hard to find. Everybody knows the constellation Cassiopeia, the big W, and the second dip in the W points right to it. Part of the constellation Pegasus lies just a short ways (visually) below the W, looking like a very long, thin V lying on its side with a bend in each spoke like knees on a pair of legs; and if you look just above the uppermost knee, the one closest to Cassi's W, Andromeda is there, looking like a very faint grey oval splotch. I can find it now without the telescope, and even that gives me the same shudders I felt when I first caught it in the lens. It scares me. Andromeda is 2 million light-years away--so what we're really seeing is how it looked 2 million years ago--and the fact that we can see it at all over that astonishing distance gives an indication of what a truly massive object it is. The enormity of it gives me the creeps. And the knowledge that it's bearing down on us--that one day our entire sky will fill with an image like the one above--is mind-blowing. There are nights I can't even look at Andromeda because the sight of it shakes me that hard. Honestly, though we can see it, I don't believe we can't really picture it, how vast and complex and full of secrets our neighboring galaxy is. And Andromeda is hardly alone in inspiring that kind of awe. I read a lot of science books and I recently finished one about the discovery of pulsars and confirmation of the existence of black holes in the 1970s and 80s. You don't have to delve far into that subject matter to find things even more frightening than a galactic crash. The very first black hole discovered--a massive X-ray emitter in the constellation Cygnus--is just terrifying. It wasn't discoverd first for no reason: it is GIGANTIC. The Cygnus X1 black hole is 7 billion times the mass of our sun and has a diameter the size of the orbit of Pluto. There's not time or space here for me to give a full explanation of black holes and what these statistics imply, but if that description doesn't drop your jaw then you don't understand it or you're not paying attention. :) I don't think the human mind is capable of truly comprehending things like galactic distance or the reality of black holes, just like we can't picture a four-dimensional object or truly understand concepts like time and infinity. And there's the tie-in to The Just Beyond. The book deals with these subjects, and the trilogy, primarily the final book, is going to involve black holes and cosmological topology in a way that's intimately integrated into the plot. And the reason for that, it will be no surprise, is my utter fascination with these concepts that strain our mental capacity. I find them every bit as awesome and humbling as the concept of God...and, like the professor Dan Hendrick in the first book, what it really comes down to is that I see them as the same thing. We don't need movies and novels to expose us to divine power beyond our ability to reason: the night sky surrounds us with it. The science fiction of its nacent years gripped me in a way that most of today's writing does not, and it's not just because I was young. Under the pressure cooker of the Cold War, with the Apollo Program placing space exploration front and center on the human agenda, and with the rash of new discoveries and speculations about concepts like black holes and extra dimensions creating a pervasive sense of dark mystery, those stories made it feel as though a reality right out of the Twilight Zone might confront us around every corner. And the thing is--if you really make an effort to understand what science has revealed over the past century--it has. I'll never be an Asimov or Clarke or Bradbury. I don't have that kind of genius. But I'm shooting at least to create a similar feeling with the Beyond books. And I will make at least one more attempt to write a solid straight science fiction novel. I'll do it as soon as I'm confident I have The Right Idea. With my science books and my telescope, the bright image of Jupiter gazing down through the window when I wake up at night, there's no lack of inspiration. :) - Mark I'm not sure Lewis Carroll had any idea what was going to happen on the next page as he wrote the Alice books  Yay! I can upload images again. The one at left makes me want to read the book. :) You may have noticed that I promised imminent release of the first chapter of The Far Beyond (to my readers group, that is). The reason I haven't done so already is that it's not finished. I have been working on it, but mainly not writing per se. Mostly what I've been up to is fleshing out the story in my head. This is solid practice--I produced The Just Beyond the same way. In my mind, planning is critical. It would be fun to make everything up as you go, and many authors have tried it. I'm not sure Lewis Carroll had any idea what was going to happen on the next page as he wrote the Alice books. :) But as a general rule, you can't craft a great novel without planning. The Just Beyond has several twists and revelations whose impact depends on setting them up earlier. And, of course, the book as a whole sets up the rest of the trilogy. I'm not saying the author should never experience surprise at where the story leads them or add unexpected content that occurs to them midway through. These situations embody the magic of writing. :) But planning the whole thing in outline or chapter form is the most powerful way to make the story coherent and convincing. It took two years to flesh out The Just Beyond before the writing started, and the idea for it first occurred to me about six years before that. Writing The Far Beyond will take much less time--I expect to have it done by the end of this summer. Partly that's because I learned a lot about how to write fast and efficiently in doing the first book, but even more it's because of the planning and note-making I did for it while writing its predecessor. It's all good, it's ALL good. :) - Mark the vast majority of games, even the shooters, cast the player in a moral role, a part in the story that in a movie would have been played by John Wayne or Gary Yesterday's post got into the current gun control discussion, and I promised to finish with my take on whether censoring video games should be part of the answer.

I didn't have a computer when I was growing up, mainly due to the fact that I was not a NASA scientist or a student at MIT. :) But I was always into games. I had all the old cardboard Avalon Hill wargames and loved them like a cheap toy with mortars and half-tracks that nobody else cared about... which they were. At an even younger age I had cap guns, squirt guns, home-made rubber band guns (remember those?), and plenty of similarly armed friends to play "war" with. We used to romp around vacant lots or horse pastures peppering each other with imaginary bullets and using dirt clods as hand grenades. All the kids did that--the boys, anyway. It wasn't the only thing we did--we played baseball and collected insects and ruined our shoes playing in the creek exactly as we had been told not to--and there was nothing particularly different or special about playing "war", "spies", "cops and robbers", "cowboys and Indians", or any other pastime that involved simulated weaponry. We didn't think of it as literal killing. We did it because it was fun. And to the best of my knowledge, none of us was ever inspired by that horseplay to gun down real people. There are some parents out there that don't let their children play with toy guns (and I respect that, though I don't agree with it), but most reading the above will view those boyhood antics as harmless. Many of those same people, however, find themselves mortified at the explicit carnage they see in video games. And they conclude, with conviction as ironclad as though they were social scientists with a solid clinical study proving the point (which they aren't), that such play necessarily warps the mind and leads to mass murder just like marijuana leads to heroin. People with that belief all have one thing in common: they're not gamers themselves. They will concede, the majority of them anyway, that chucking dirt clods at your schoolyard friends and yelling "kaBOOM!" is just normal kid stuff, but they view playing a video game with molotov cocktails made out of pixels of light as a moral hazard. (Word: I'd rather be fragged by a rocket-propelled grenade in a computer shooter than beaned in the head with an actual dirt clod. For reals.) All that video violence HAS to have a deleterious effect, they're sure--to them it seems self-evident. Their perspective is perfectly understandable--and completely wrong. As evidence, they'll point out that many of the disturbed young men who have carried out mass killings in the past few years were avid video gamers. And this is entirely true. It's bound to be, because the vast majority of kids these days ARE avid video gamers. The fraction of them, even the fraction of those who favor weapons-oriented games, who go on to shoot people in real life is infinitessimal. The alleged cause-and-effect simply isn't there. Healthy, mentally balanced people do not commit senseless murder--whether they are gamers or not. Those who do perpetrate such atrocities are almost always afflicted with some form of psychopathology--again, whether they are gamers or not. Video games may focus the morbid tendencies inside the already sick minds of those individuals, I can't say that they don't. But games will NOT turn a normal human being into a frothing killer. We have laws against the possession of guns by people who would represent an inordinate risk by having them--children, felons, and the mentally incompetent. We restrict access to certain ingestibles and forms of entertainment in a similar way. I support that approach, and see no reason why it shouldn't extend beyond movies, magazines, alcohol and tobacco to include games as well. I also see no reason games should be carved out of that mix for especially severe treatment. I play a lot of computer games, and I can tell you I've never seen anything in a game that surpasses the brutality in movies like Braveheart or A Clockwork Orange, to name two completely random examples. Yet people who would never support banning that kind of motion picture feel it's blatantly obvious that the exact same content should be forbidden in games. How are they able to hold these objectively inconsistent views? Because they're not gamers. Because they're making assumptions regarding something they know nothing about firsthand. The common argument for singling out games is the element of participation. Again, this is a misunderstanding of the medium arising from ignorance. The opposite is actually true. I find violence in movies much more offensive and emotionally stressful than in games BECAUSE of the participation element. Just because I can hack a computer character to bits with a machete doesn't mean I will, and in fact I have played through Far Cry 2 dozens of times having never once hit an enemy with my machete or the flamethrower. I even feel bad when I hit them with a bullet anywhere except the head, which produces an instant and presumably painless fictitious kill. The game doesn't make me someone I'm not, in fact I conduct myself morally even though I'm completely aware the events on the screen are not real. That's the style of play I find enjoyable. By contrast, when brutality happens in a movie, I'm helpless. There's not a thing I can do about it except sit by and watch, turn it off, or get up and leave. In a game, I can actually influence things for the good. And while many non-gamers may not be aware of this, the vast majority of combat games cast the player in a moral role, a part in the story that in a movie would have been played by John Wayne or Gary Cooper, Mel Gibson or Orlando Bloom. I'm not a blind advocate on this issue and I concede that games can have a desensitizing effect. Something that seems horrifying the first time you experience it doesn't have the same impact the 20th time down the road. But the same is true of any cultural influence--movies, song lyrics, oil paintings, real-world war coverage on CNN. Games are not some special case where this effect is singularly onerous. And again--as with every other stimulus mentioned in today's and yesterday's posts--this desensitization does not make murderers out of mentally healthy people. Most rap music fans don't shoot police officers or beat their girlfriends and most gamers don't go on killing sprees. In both cases, the few who do are psychological outliers--and this, not their choice of entertainment, is where our concern belongs. Games are not the problem. Guns are not the problem. Games and guns in the hands of the mentally ill are the problem. And that's where solutions must aim. The idea of taking Halo and Far Cry off the market in response to incidents like Aurora and Newtown is just stupid. Worse, it has no chance whatsoever of fixing the problem. For every lone, sick kid who plays Hit Man and then shoots up a school in real life, there are millions of kids who find such games entertaining and go on to peaceful, productive lives. And we should focus this discussion where the real problem lies. Indiscriminate censoring of video game content would make a lot of (clueless) people feel good, but it wouldn't actually do good. It would merely punish lots of positive, well-adjusted players who enjoy this truly harmless pastime. - Mark It's no different than outlawing hard liquor in an attempt to stop alcoholism and drunk driving, which kill more than twice as many people as guns do every year If you're going to blog every day--and I think you have to if you expect readers to patronize your page faithfully--there are going to be days when you have to stray off topic at least a little in order to write something interesting. People reading your blog presumably would like to know something about you personally, whether they agree with you or not, so I don't view this as a complete abrogation of the blog's purpose. And so, with nothing new on the book(s) since yesterday and since gun control is in the news lately, and my view on it doesn't seem to fall neatly into the mainstream positions being articulated, I'm going to share my thoughts on that.

There is a tie-in to the books, by the way. In The Just Beyond Michael Chandler is assailed or threatened by gun-wielding enemies more than once, he is even handed a weapon to use for good purposes at one point, but it is made clear he personally abhors them and not only can't shoot, but doesn't want to learn. This isn't meant to convey a moral judgment; for one thing, Michael's bacon is saved a couple of times because his allies do use guns, and for another, I don't share Michael's disdain for them. I do however, hold deep respect for his tendency to use finesse instead of force to solve his challenges. The right to bear arms expressed by the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, at the time it was written, was a countermeasure against the founders' experience with the British government it had broken away from. In Britain then (as largely today), guns were mostly restricted to the constabulary and the military. This reflects the political maxim that citizens only have the rights the government gives them. While in a way that can be interpreted as true of any nation, America was founded on the opposite principle--that the government has only the rights granted to it by the people. The flip side is that the citizenry retains unfettered freedom in all respects not expressly outlawed. It certainly comports with the founders' conviction that as a general matter, the government should never be able to subjugate its population by brute force. Times have changed. Today there is no risk of a British attack or that the U.S. government as a whole will turn on its people. Weaponry has come a long way too. In 1776 and for much of the century that followed, firearms were clumsy, inaccurate, and only capable of a single shot between tedious loadings. Modern small arms can fire dozens or even hundreds of rounds in seconds. What would the founding fathers have done with this scenario? I don't think it would have mattered. The premise that government should be hands-off to the greatest extent practicable is not strained by these developments. Besides, in those days men often carried multple pistols so they could fire in quick succession, and the government didn't outlaw that. CNN's Piers Morgan (not surprisingly a Brit) likes to ask why people need guns, impliying that in the absence of need (as he defines it) the government should prevent their having them. He's hit the nexus of the issue and the key difference between the British and American philosophies. The Constitution does not reserve to the government all powers not expressly conveyed upon the public. It does the reverse. And this is what infuriates me most about gun control: the notion that law-abiding citizens, which include the overwhelming majority of gun owners, should be denied some right--any right--in an attempt to prevent criminals, societal outliers, and the mentally ill from doing bad things. It's no different than outlawing hard liquor in an attempt to stop alcoholism and drunk driving, which kill more than twice as many people as guns do every year. Freedom is not free, and these are unfortunate but unavoidable consequences of a society with individual liberty at its foundation. The current debate came as a direct result of the Newtown school incident, fortified by the Aurora theater massacre, the Oregon mall shooting, and the Gabrielle Giffords assault. It follows that any gun control measure should face this litmus test: would it have prevented these tragedies? I lean toward gun owners' rights, although I could support a ban on the most advanced military weapons and magazine capacities, and I definitely support gun show checks provided a fast, practical electronic system is put in place that doesn't unduly delay the purchase. But let's get real. Congresswoman Giffords and the other victims of that incident were shot with a pistol bought by a mentally ill man whose purchase was possible because he had never been declared mentally incompetent by a judge and so passed a background check. An assault rifle ban would have been irrelevant and the background check was ineffective. Ideally a check with accurate results would have prevented the sale, but where was accurate information about his mental state supposed to come from? He had never been medically diagnosed nor clashed with law enforcement. How could any background check, even a more robust one, have turned this up? The suspect in the Aurora movie theater was also mentally ill, had stolen the weapons, and used a pistol, a shotgun, and an assault rifle, only the last of which might have been banned by current proposals. No amount of background checking can prevent weapons from being obtained by theft, nor would proposed magazine limits have reduced the carnage. Unlike a pistol or rifle, a short range shotgun blast creates a wide area of damage like a hand grenade, so an assault weapon ban wouldn't have worked; every point in the theater was within effective shotgun reach, and he could have carried two of them if denied his AR-15. The Oregon mall shooter also had stolen his weapon, and left no indications of why before killing himself except having seemed detached and listless during the week before. It's not clear whether he was mentally ill, but he clearly was in some kind of altered mental state and over a month later, following an intensive investigation, the police have found no motive. What in any of the proposals is supposed to be able to prevent this? Paradoxically, the Newtown attack, whose horror was the specific trigger that unleashed the debate, is the definitive demonstration of the ineffectiveness of the most commonly proposed gun control measures. He stole his weapons; he was mentally ill; the owner of the guns he used had passed a background check; in addition to an assault rifle he had two pistols with numerous backup clips, which by themselves could have killed every victim slain without reloading or by reloading with smaller clips between the principal's office and the classroom; and the school had extraordinary, robust visitor entry measures in place which the shooter easily overcame. Which of the current gun control proposals would have unwound this attack? What strikes me most about the discussion is that while it's universally acknowledged that the perpetrators in each of these cases was mentally ill--only the Oregon mall case being a possible stretch in this regard--yet the solutions they offer are targeted at sane, clear-thinking and law-abiding citizens. Stop right there! Banning military slaughter gear and requiring gun show checks sounds great, it feels like doing something about the problem, but IT HAS NO EFFECT AT ALL ON THE BRAIN DISEASE THAT ACTUALLY CAUSED THESE MASS MURDERS. THE PROBLEM IS MENTAL ILLNESS. These measures wouldn't have prevented these killings. In the Newtown case, a raft of similarly serious measures FAILED. So are the proponents serious about addressing the issue, or are they just using these tragedies--perhaps unconsciously--as an opportunity to promote a slightly oblique agenda? And another thing, as they say :) --the supposed tie-in to electronic games is utterly, infuriatingly bogus and I will debunk it in tomorrow's post. Stay tuned! - Mark |

Once upon

|

| The Just Beyond |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed