Michael swallowed. It was all he could do to hold back tears of his own I'm about 2/3 the way through the publisher's edits now and should be done no later than the middle of this week. I underestimated somewhat the extent of their changes and the amount of effort it was going to require from me--there are after all more than 600 pages, with at least something altered on almost every one. But my initial assessment remains valid that nothing fundamental is involved and the vast majority of it is barely noticeable stylistic tweaks. Most the "on every page" comes from alterations like inserting a space before ellipses or converting the "M-dash" style I used to the one the publisher prefers.

They are having me make a small number of substantive revisions, and I thought you might like a practical example. Below is the most significant change I've made so far (just three paragraphs long). They felt that Michael's reunion with his childhood pet Alex, the Siamese cat who becomes a powerful panther in the Afterlife, needed some emotional foundation. So I have added this little subsection into the scene in Chapter 8 where Michael ends up paying for a stranger's pet bird to have surgery. "Beaker" is the little parrot involved. "Michael swallowed. It was all he could do to hold back tears of his own. His comprehension of the man's suffering went beyond empathy. It evoked acute memories of a tightly bonded pet in his own life, an atypically warm and placid Siamese cat named Alex that had been rescued by his mother when a co-worker moved to an apartment that forbade animals. Like Beaker, Alex had been a family pet not intended specifically for Michael or his brother, both in grade school at the time. And like Beaker, the cat had nonetheless of its own accord, and for reasons that defied discovery, adhered with obvious preference to one person in particular: Michael. It had matured into a joyous, life-affirming symbiosis. Wherever Michael went the cat could be found, perfectly content as long as it could be near him. Alex had established ingenious habits to manifest his affection in ways unobtrusive yet intimate, nesting himself in Michael's lap while he watched TV, squeezing into the gap between the chair and the small of Michael's back at homework time, draping himself on Michael's pillow each night like a set of warm, hypnotically breathing earmuffs around his master's head. Then, when the boys were in high school, Alex had developed lesions. A patch of skin on his left hindquarter had erupted in a bloody sore the size of a quarter, which gradually grew into an obviously agonizing malignancy affecting the entire limb. By that time the cat could only drag the leg around dysfunctionally. Nothing could be done, and at last Michael's near-hysteria at the thought of life without his companion was overtaken by a resolve to end his misery. Michael had insisted on accompanying his friend to that terminal appointment with the vet, and as it turned out, when the day came only Michael was able to go. Alone in the parking lot afterward, Michael had collapsed onto the asphalt in a seizure of anguish, his keys hanging from the car door, such a forlorn spectacle that the receptionist had abandoned her desk to come out and hold him reassuringly until he regained enough composure to drive." It's great after such a long emotional relationship with the book to be experiencing this tangible evidence that it really is going to be published. The work that remains is taxing, but it's a good kind of work to have. :) - Mark

0 Comments

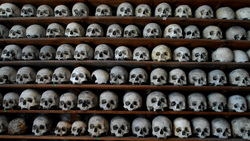

108 billion humans have lived since 50,000 BC  The details of the overall plot for the Beyond trilogy are reaching critical mass. Yes, I should be focusing mainly on the book I'm writing, the second volume in the set called The Far Beyond. And I am. But as that part of the story fleshes out, it necessarily creates ties to The Just Beyond and implications for the final book. And this is important, because it helps assure two things: 1) that the narrative will maintain an intimate, logical, and consistent flow, and 2) that I'll finish writing it. :) Even with publication of the first book, writing the other two is a daunting challenge. Writing is a struggle for me to begin with, and on top of that I am perpetually aware that one well-received book is no guarantee for the others, even as they follow the over-arching theme begun in the first. With regard to The Far Beyond specifically, the middle book of a trilogy is often the weakest, and I'm consciously working to overcome that phenomenon. I mean, The Two Towers is entertaining and critical to Lord of the Rings, but it certainly lacks the excitement of The Fellowship of the Ring or the satisfaction of Return of the King. Which brings me to a point about writing. Lord of the Rings is my unqualified favorite work of fiction, and its appeal sets the standard to which I aspire. An unfortunate side effect, at least for me, is a tendency to write something that parallels LOTR to an uncomfortable degree. According to a calculation by Google, the total number of books ever published (mostly in the modern era) is around 130 million. The Population Reference Bureau calculates that a total of 108 billion humans have lived since 50,000 BC (equating to one book per every 831 people, which doesn't account for writers who produce multiple books). The arbitrary starting point makes this a dicey statistic, though: somthing like modern civilization is said to have commenced only about 10,000 years ago when the last great Ice Age ended, or even later with the Ancient Egyptians around 5,000 BC. On the other end of the spectrum, human ancestry can be traced to around 100,000 years back or as far as 2 million, depending on how you define human. Which is a tedious and twisting setup for the statement that it's devilishly hard to come up with an original story. At the archetype level, every conceivable scenario has been written about over and over and over, and probably better than I could hope to do. How can one writer among a world population of 7 million generate something, if not a completely untried premise then at least a distinctive variation, that hasn't been done before? Even in heavily trodden, formulaic genres like Western and Romance, publishers want to know what makes your book stand out. And as a first-time author, you'd better have an answer. When that question came, I told publishers that what distinguished The Just Beyond and its successors was a fearless depiction of the Afterlife. As noted on this site's home page, I aimed to transcend the prevailing approach of leaving the nature of the world beyond death "to the imagination". Nothing in fiction is more disappointing than a story that leads you down the garden path only to invoke this cop-out at the end. I've never read another book that handles this subject quite as I did, and my research didn't turn up anything too dangerously close...but how can you know for sure? And in spite of my good intentions, that old compulsion to ape my favorite material seems to have slipped in while I wasn't looking. I began this posted not intendng to compare the Beyond books with Lord of the Rings. Yet as I consider it, some parallels pop out. In both sets the protagonist is an unassuming personality with empathetic and courageous tendencies, capable of extraordinary feats when called upon. Both tales begin with some necessary background and then launch a desperate, stealthy flight hounded by ghoulish enemies. Upon reaching a safe haven more of the plot is revealed, sending the hero on an even more harrowing path that results in a critical death. Powerful truths are revealed, unlikely allies emerge, formidable enemies are bested, and the most fearsome foe of all is finally confronted in an epic battle involving a sword of immense power. Prominent side characters are wed to their loves, and our hero sails off to a surprising but well-deserved reward. I never intended nor even recognized these shared elements; obviously my subconscious had the upper hand. Ah, well. Any originality issues raised by my trilogy probably won't matter, since the first book has been judged viable enough to print. That's good, because I'm not sure I could do better. If I'm fortunate enough to develop a solid writing career, I'll certainly try. In the meantime, faintly echoing a classic is hardly the worst problem I could have. :) - Mark it wasn't the usual feeling of being suddenly alert; something physical woke me  Stick with me on this one, it's not another space jaunt even though it may seem to start out that way. Although... I get up early every day, typically between 4 and 5 AM, sometimes earlier. This morning I woke up at 2:30, and I've learned when that happens to just go with it. Left to its own my body seems to need about five hours' sleep most nights, though sometimes longer. There's no reason to fight it with my flexible existence down here. But this morning it wasn't the usual feeling of being suddenly alert; something physical woke me. I'll get to that in a minute. The first thing I noticed, once I realized that, yes, I wasn't going back to sleep so I may as well get my feet on the floor, was a light outside the house. We have a motion-sensor flood light in the yard, and when it goes off in the middle of the night it's typically a deer wandering through. It's not intrusive enough through the bedroom windows to wake me up by itself, but it is plenty bright. And the light I could see being cast downstairs from the kitchen was too bright for any natural light. Except it wasn't. You'd think after four years I'd recognize it, but it turned out the security light was not on. No light was. What I was seeing was coming purely from the Moon. That's how dark the night sky is here. It's shocking when you come from a city that never truly sleeps, unlike Brookings where there's not a single 24-hour business in town. But don't get the impression our house is swathed in black. It never is. The yard is completely surrounded by rain forest so thick we can't see any of our neighbors' homes, but even on moonless nights, the starshine is enough to make out most features on the property. When the Moon is out you could literally read by it. It has fooled me into thinking the flood light was on many times, but even so, it's so unexpected that it still catches me after all this time. But it wasn't the Moon that woke me. I had been dreaming of a skiing trip with my grandfather who passed away in 1999. We were just headed to the slopes, and he was handing us all something--it looked like a chunk of dry ice, though I'm not sure why that would be. Its purpose though was clear. The ski resort was at high elevation, and breathing the fumes coming off these chunks made up for the paucity of oxygen and let you breathe normally. My grandfather was that kind of man--generous, no-nonsense, and always prepared. When I woke up, the reason for the dream was apparent. One of my sinuses was so closed up I could only breathe on one side. A few minutes of traipsing around the house upright cleared that, and I was left with the dream's deeper meaning. I held a special fondness for my grandfather. I mentioned before that he was the only person who ever read my first novel manuscript. But that wasn't the source of my regard. He was the most fearless and forthright man I ever met, imbued with unshakeable integrity. (Happily, those traits were inherited by my father.) He could seem harsh, but only because he always spoke the plain truth. And the truth hurts, as they say, at least a good share of the time. Our personalities were fiercely opposed, but we still had a lot in common. He was a huge fan of science fiction, which now seems anathema to his knothead-intolerant demeanor. In fact it was he who turned me on to sci-fi, in the form of paperback novels left on a bookshelf in a lakeside cabin he built with help from my dad and his brothers. I still have two of those books that I stuffed in my suitcase at the end of a visit there. A decade and a half later, my grandfaher's absence still leaves a void in the world. I wish he could have met the man I have become. I hope someday he will. -Mark A billion years is a very long time--almost twenty times as long as it's been since the dinosaurs went extinct--but compared to Eternity it's not even a nit.  The Just Beyond asks what has always seemed to me a natural question, deceptively hard to answer. If there really is an afterlife and you're fortunate enough to get there...what are you going to do? The question is probed at greater length if not more eloquently in the book, but to boil the problem down, it goes something like this. When you think about it, everything we do in this mortal life is bound up with our physical bodies. Note, I didn't say everything we care about, I said everything we do. I can think of plenty of moral and artistic values we care about that seem primarily spiritual. Back to that in a moment, but to finish the first point. Suppose, as most believers do, that in the afterlife the body and its requirements are transcended. No more pain, no more injury, no more disease, no more fatigue, et cetera. Having surpassed the physical, there's no need or reason to eat or drink, or sleep, or arrange for shelter, or have sex. Presumably no babies are born in the afterlife, so that last is doubly useless. (Is that really an afterlife I want to live in? I'm not so sure. lol) You don't need money, because you don't need anything at all just to survive, so you surely wouldn't work at anything you didn't find worthy on its own merits. But would you even do the worthy things? For a while, sure, assuming you could; maybe for a very long time. If you've always loved skiing, maybe you climb the highest mountain and schuss down it one zillion times. No lift needed, you wouldn't get tired and you'll never run out of time. But what's the cutoff point? At a zillion and one, have you finally done down every possible path, had every possible experience, maybe had each of them a thousand times, or a million...does the compulsion to do this at some point stop? The same is true of any activity. How many songs can you write or paintings can you make before you're out of ideas or enthusiasm or both, a billion? A trillion? And what are you going to paint or sing about? If the Earth is behind us, the sick are made well, there's no more poverty, war, hard luck, or romances gone bad, what's your material? Even if you have an answer, how long can you stretch it out? A billion years is a very long time--almost twenty times as long as it's been since the dinosaurs went extinct--but compared ti Eternity it's not even a nit. Most people when they think of afterlife envision themselves communing with loved ones or acquaintances long lost. That is a terribly noble and worthy picture. But think about it. After a while, and I mean a long, long period of doing that...what are you going to talk about? There won't be any family secrets or celebrity scandals. There won't be any politics or issues of general concern. There won't be any news, either about the world or about you and your loved ones; given enough time, everything that can be said will have been, and there's no more coming. No marriages or births or deaths or misfortunes or runs of increble luck. All that stuff arises from the mortal human condition. I know people who imagine themselves just standing in the Heavenly pews singing praises to God as their afterlife activity. I'm not going to argue with that, it sounds nice, wholesome, worthwhile, enchanting, and probably well-advised. :) But the same analysis applies even there. Are you going to do nothing but sing in church for all eternity? Is that really what your whole existence was all about? The Just Beyond begins to answer this question, and the trilogy when complete will give the most logical and satisfying answer I've been able to work out--and I've given this a lot of thought. :). Even so, I've been harboring a terrible secret. Because I realized somewhere along the way that my answer, as reasonable and carefully constructed as it was, ultimately fell to the same criticism I've outlined above. My scenario works for a long time, a very long time, and explains everything from the purpose of mortal life to the ultimate fate of good and evil...but then, after all that has been said and done, philisophized about and settled...in comes Eternity again. And it's just about impossible to think up a scenario that truly conquers ALL time. I knew this, and I thought the books would come close enough to feel they had achieved it as far as one reasonably could, and I had set the problem far aside, on a small table in a dark basement room in another house, never to be thought about again. :) And then, suddenly, it came to me...an even better way. An answer that went beyond my hard-crafted paradigm, as full and coherent as it was. An answer that seems like it could be eternal, and if not, comes close enough to blur the distinction between perfect and very, very, very, very good. :) What is it? Read the books. I hate to leave it at that, but on the other hand this is the sort of thing, obviously, that can't be fully revealed until the final pages of the final book. With any luck I'll have that written by the end of next year. Meet you at Beyond All Else, and you can let me know how I did. :) - Mark The Cygnus X1 black hole is 7 billion times the mass of our sun and has a diameter the size of the orbit of Pluto.  I've always been fascinated with the night sky. As a kid I used to take my guitar out into the front yard and night to sit on a brick step and play where nobody could hear me but the stars. It was an inspiration like no other. Now I have a decent amateur telescope, a Meade Polaris 6-inch reflector, and live in one of the least populated areas of the country where the heavens shine in all their glory undiluted by city lights. I grew up in a small town with relatively dark skies, but living in Seattle for decades I had forgotten just how brilliant and stunning the cosmic scene could be. One of the first things I did when we got settled down here was grab my star atlas and look for the Andromeda galaxy. It's the one in this picture, the iconic Hubble Space Telescope image, the galaxy we tend to picture in our minds when the word is mentioned. Among the billions of galaxies we know about, Andromeda is remarkable in several ways--unique, in fact. First, it is the closet major galaxy to our own (discounting two small satellite galaxies that revolve ours like moons). Second, it's the only galaxy outside our own that can be seen with the naked eye--though you need ideal conditions and a good idea both where to look and what to look for. Third, and this is the one I find the most mesmerizing: Andromeda is not receding from the Milky Way. It's heading toward us. The world was shocked when Edwin Hubble discovered in 1923 that some of the amorphous blobs in the night sky were actually "island universes" separated by unimaginable distance from the one we live in. The aftershock was just as great six years later when Hubble found that the univese was expanding: every galaxy in the cosmos was racing away from us at tremendous speed. Well, not every galaxy. Andromeda, of the same class and somewhat larger than the Milky Way, is on a collision course with us. It's going to happen. One day in the distant future Andromeda and the Milky Way will collide, eventually fusing into a single system with each of its constituents' original shapes obliterated by the crash. It's nothing we should worry about though: significant gravitational contact between the galaxies is four billion years away, and by that time our sun will be starting to run out of hydrogen and preparing to explode. If the human species survives to see the galactic fusion, we'll need to have found someplace else to live.) Andromeda isn't too hard to find. Everybody knows the constellation Cassiopeia, the big W, and the second dip in the W points right to it. Part of the constellation Pegasus lies just a short ways (visually) below the W, looking like a very long, thin V lying on its side with a bend in each spoke like knees on a pair of legs; and if you look just above the uppermost knee, the one closest to Cassi's W, Andromeda is there, looking like a very faint grey oval splotch. I can find it now without the telescope, and even that gives me the same shudders I felt when I first caught it in the lens. It scares me. Andromeda is 2 million light-years away--so what we're really seeing is how it looked 2 million years ago--and the fact that we can see it at all over that astonishing distance gives an indication of what a truly massive object it is. The enormity of it gives me the creeps. And the knowledge that it's bearing down on us--that one day our entire sky will fill with an image like the one above--is mind-blowing. There are nights I can't even look at Andromeda because the sight of it shakes me that hard. Honestly, though we can see it, I don't believe we can't really picture it, how vast and complex and full of secrets our neighboring galaxy is. And Andromeda is hardly alone in inspiring that kind of awe. I read a lot of science books and I recently finished one about the discovery of pulsars and confirmation of the existence of black holes in the 1970s and 80s. You don't have to delve far into that subject matter to find things even more frightening than a galactic crash. The very first black hole discovered--a massive X-ray emitter in the constellation Cygnus--is just terrifying. It wasn't discoverd first for no reason: it is GIGANTIC. The Cygnus X1 black hole is 7 billion times the mass of our sun and has a diameter the size of the orbit of Pluto. There's not time or space here for me to give a full explanation of black holes and what these statistics imply, but if that description doesn't drop your jaw then you don't understand it or you're not paying attention. :) I don't think the human mind is capable of truly comprehending things like galactic distance or the reality of black holes, just like we can't picture a four-dimensional object or truly understand concepts like time and infinity. And there's the tie-in to The Just Beyond. The book deals with these subjects, and the trilogy, primarily the final book, is going to involve black holes and cosmological topology in a way that's intimately integrated into the plot. And the reason for that, it will be no surprise, is my utter fascination with these concepts that strain our mental capacity. I find them every bit as awesome and humbling as the concept of God...and, like the professor Dan Hendrick in the first book, what it really comes down to is that I see them as the same thing. We don't need movies and novels to expose us to divine power beyond our ability to reason: the night sky surrounds us with it. The science fiction of its nacent years gripped me in a way that most of today's writing does not, and it's not just because I was young. Under the pressure cooker of the Cold War, with the Apollo Program placing space exploration front and center on the human agenda, and with the rash of new discoveries and speculations about concepts like black holes and extra dimensions creating a pervasive sense of dark mystery, those stories made it feel as though a reality right out of the Twilight Zone might confront us around every corner. And the thing is--if you really make an effort to understand what science has revealed over the past century--it has. I'll never be an Asimov or Clarke or Bradbury. I don't have that kind of genius. But I'm shooting at least to create a similar feeling with the Beyond books. And I will make at least one more attempt to write a solid straight science fiction novel. I'll do it as soon as I'm confident I have The Right Idea. With my science books and my telescope, the bright image of Jupiter gazing down through the window when I wake up at night, there's no lack of inspiration. :) - Mark Inquiring minds want to know. Lazy writers won't tell you.  What generated the basic premise in The Just Beyond? Frustration. There has been plenty of fiction about the Afterlife, but it tends to sort into three categories. The first, let's make up a term, is "gothic immortality." These are the vampire and similar works of Anne Rice, Twilight, Underworld, Being Human, and so on. They're hugely popular and definitely entertaining, but they don't really define an Afterlife per se. What they define is states of eternal life, whch is not the same thing. And while they often include a tremendous amount of history and march to a consistent set of "rules", they typically do not elucidate what I consider the most important question: why. Not how they came to be what and where they are; that is universally covered. What's missing is an overarching explanation of why they should exist at all. The second category is what let's call "Earthlike." A prime example is the movie Defending Your Life, where Albert Brooks goes on trial in an environment indistinguishable from the mortal world and winds up running after a bus bound for Heaven, which itself drives into that same kind of mist as described below. The typical proposition is that the Afterlife only seems grounded in the familiar because the characters aren't able or ready to grasp its reality. They're seeing a metaphor they can understand and not the true environment. That I could almost buy, but what is the reality? Inquiring minds want to know. Lazy writers won't tell you. Last and most prevalent is the "fog of death", a.k.a cheating. :) The Afterlife is barely shown if at all. This lets the writer off the hook from depicting a complex Afterworld or explaning why it is as it is. Dead characters disappear into mist, fade out, or simply vanish, giving little or no glimpse of what lies beyond. Daniel Radcliffe does this in the last Harry Potter movie and his later The Woman In Black. (By the way, watch the 1989 original of that movie if you want to experience the prickliest feeling you've ever had at the back of your neck .) There are at least two reasons for this. First, to define the Afterlife in rich and specific detail, writers run the almost guaranteed risk of alienating or offending potential readers who consider their own vision of life after death to be inviolate. Second, working out the details of a selt-consistent Afterlife is hard. What exactly is required to get in? Do people sleep, eat, or have sex? If so, why? What other things do they do? Eternity is a very long time. How long would you be content to do nothing but flit about in the clouds on angel wings visiting departed family and friends - a year? 10 years? 100? A million? A billion? How long would it take to pursue your every aspiration, and once you're finished, what would you do then? These questions are left begging in most Afterlife fiction, but they can be answered. It just takes courage: the willingness to develop a coherent image and then bear the bitter assault of a multitude of offended detractors. Richard Matheson's What Dreams May Come gives a complete, consistent, and rational explanation (as will the Beyond Trilogy by the end; the first book has only cracked open the topic), and I respect it immensely. None of its critics, when you weigh them objectively, have a vision as logical or robust. The Afterlife in The Just Beyond overlaps some of Matheson's picture, though not so much that originality is lost. I wish there were more like it. I don't believe that Matheson's concept or mine literally reflect reality, but they might. Isn't it a good thing to have such possibilites afloat in the marketplace of ideas? - Mark  Genre wasn't an issue during the writing. There was a story to tell, and that was that. But when it came time for submission to agents and publishers, genre was critical in choosing the right ones--because most agents and publishers handle a particular set of genres and don't want to see anything else. I decided "Paranormal Fantasy" was the closest fit among industry standard categories. But it really is a hybrid. There's a strong Science Fiction element, with most of three chapters devoted to that, but the pervasive theme involves angels, demons, and supernatural apparitions. It's not a traditional Romance, but the heart beating at its core is an aching love story. And, of course, the title and the book overall concern the nature of the Afterlife. But I had to pick one genre in the hope it wouldn't be rejected out of hand, without even being read, as too unfocused to market. I expect it will be assigned to the Sci-Fi and Fantasy shelves, and that's where it belongs. I plan to do a straight Sci-Fi book once the Beyond Trilogy is done, and I already have the premise worked out. It will be called Space Radio, and will tell the story of a lone man with a small private starship, coursing through the galaxy listening to broadcasts from the planets he passes. I'm fully aware of the plausibility hazards implicit in that description, but there's a lot more to it and I've resolved most of the problems in my head. But enough of that; I have two more Beyond books to do before I can even think about what comes next. I hope the stunning (in my view) climax at the end of the trilogy will sell the whole set well enough to make me a fulltime writer. One can dream, right? And the best fiction writers, I feel, are the ones with their heads in the clouds. -Mark |

Once upon

|

| The Just Beyond |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed